Forest Research Institute Malaysia, Malaysia

Every day throughout the world researchers, scientists, inventors, and entrepreneurs are coming up with new technologies and inventions, but in reality many of these are never marketed (New Products: The Key Factors in Success, 2011 and Savonia University of Applied Sciences, 2011). Technology transfer – disseminating and transferring technologies, skills, knowledge, or manufacturing methods through patent licensing – is an important tool that can help commercialize these innovations (World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO)).

For emerging economies and developing countries technology transfer is a significant means to increase economic development (Institute of Behavioral Science, 2004). In many cases technology transfer occurs from universities or research institutes to industrial partners and with the financial assistance of a country’s government (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, 2001) through a Technology Licensing Office/Organization (TLO), WIPO).

Malaysia is a country that has emphasized the important economic role of technology transfer (Institute of Technology Management and Entrepreneurship, 2006). One government organization – the Forest Research Institute Malaysia (FRIM) – took advantage of the country’s conducive climate for technology transfer (Greg Felker and Jomo K.S., 2007 and (FRIM), 2014) to develop, patent, license, and commercialize a new timber drying and processing technology – called HTD – that does not use any chemicals or preservatives (FRIM, 2013).

Research and development

Timber from Malaysia – particularly rubberwood – is a vital resource for the country’s economy and one of its main renewable timber exports (Government of Malaysia). Before timber is ready for commercial use it typically undergoes two processes: chemical treatment by adding preservatives and then drying (either by air or heat). Chemical treatment helps prevent fungi and pest attacks while drying ensures the timber is more durable and dimensionally stable. Various chemicals are used in the treating process, and in Malaysia most timber is treated with preservatives based on borates, which are naturally occurring minerals containing the element boron (Industrial Minerals and Rocks, 1994).

Europe represents a major market for Malaysia’s timber products and the country’s exports account for nearly half of all timber used in furniture manufacturing in Asia (FRIM, 2007). If something were to threaten these exports, the Malaysian timber industry could face some serious setbacks (Government of Malaysia, 2007). One risk appeared in 2003, when a proposal was made to the European Commission (EC) to classify borates used in rubberwood processing as Reprotoxic Category 2 (Government of Malaysia, 2007), and the EC subsequently published its intention to do so a few years later (World Trade Organization (WTO), 2007).

Once a material is classified into Category 2, products must carry a skull and crossbones label (Government of Malaysia, 2007) and cannot be marketed to, or used by, the general public (Official Journal of the European Communities, 1998 and EC, 2008). In Malaysia, borates treatments are used in most drying processes (FRIM, 2013). With such pervasive use, the inclusion of borates in Category 2 could reduce consumer confidence in Malaysia’s timber industry (Government of Malaysia, 2007). To solve this problem, FRIM researchers sought to invent a new method that would eliminate the use of borates during the treatment process of timber products (FRIM, 2013).

IP management

In an email discussion with the WIPO Japan Office (WJO), Mr. Syed Othman Syed Omar of FRIM explained that each Malaysian government agency and institution makes their own decisions on how to best implement the country’s National Intellectual Property Policy, which was adopted in 2007 (NIPP, MyIPO). In the case of FRIM, their Strategic Plan 2011 – 2020 states that a licensing program is an integral part of protecting the institute’s IP rights (IPRs) and commercializing output. Indeed, Mr. Omar told the WJO via email that the institute manages its IPRs via licensing agreements for full-scale commercialization or option agreements, which allow a company to try out FRIM technology before officially committing to a license agreement.

Financing and partnerships

Supporting the country’s efforts is the Ministry of Finance Malaysia (MOF), which provides financial support for technology transfer through other government initiatives and entities (FRIM, 2014). As Mr. Omar explained in a presentation at the WIPO Singapore Office, MOF serves as a financial backbone for many of these entities. For example, the Cradle Fund Sdn Bhd (Cradle), a non-profit organization (NPO) under MOF, provides grants for business building and commercialization efforts for entrepreneurs in fields including software development, biotechnology, and renewable energy (according to Cradle).

In early 2014 MOF launched the Malaysian Global Innovative and Creativity Center (stylized as MaGiC), which, according to the Center, aims to make Malaysia the startup capital of Asia. In an email interview with the WIPO Japan Office, Mr. Omar explained that Malaysia’s NIPP is an agenda that is driving the country to an innovation-based economy and facilitating technology transfer, from idea to commercialization, through entities such as Cradle and MaGiC.

FRIM is an example of this initiative, as it develops technologies and products that support the sustainable management of forests and related industries (according to FRIM). Those that have potential are transferred to relevant government agencies for funding (through Cradle, MaGiC, or others) and eventual commercialization, such as HTD. Although there have been challenges over the years in accessing funding (as pointed out by FRIM representatives), developing and commercializing the HTD technology has proven that the various funding opportunities and partnerships available with Malaysian government entities can result in the successful transfer of intellectual property (IP).

Invention and patents

In 2007, FRIM’s R&D resulted in of a new method for treating rubber lumber using high temperature drying (or HTD), that, according to FRIM, eliminates the use of chemicals such as borates, reduces processing time by more than seventy-five percent, and enhances lumber stability. Instead of using the traditional two-step process of treatment and drying, FRIM’s invention combines these into one step by utilizing a novel high temperature drying method.

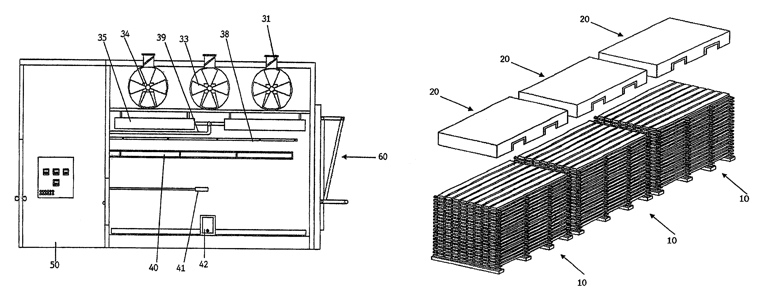

FRIM’s innovation comprises of six steps: (1) stacking the timber; (2) restraining the timber with an evenly distributed load; (3) subjecting the timber to a steam environment of not less than 95°C for 6 to 12 hours; (4) drying the stacks of timber in an air stream that is not less than 120°C in a kiln; (5) subjecting the timber to a second round of steam heating; and (6) cooling the stacks of timber in an ambient air temperature stream.

Opposed to typical kilns used for timber drying, the kiln used can be made in varying ways, but must be constructed to meet certain criteria, such as the inclusion of a heat source, a means to exchange the heat to maintain a stable and sustained temperature environment, a means to maintain a predetermined equilibrium moisture content within the chamber, and a way to generate air streams.

Implementing steam and high temperature heating allows the timber to undergo processing without the need of borates, and its versatile nature means that it is also suitable for the lighter density hardwoods that make up a good percentage of the Malaysian timber industry (Commonwealth Forestry Association, 2014). As the invention was refined over the ensuing years, in 2010 FRIM filed a patent application in Malaysia (#149935, granted in 2013) and an international patent application using the WIPO administered Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) system. Furthermore, the organization filed patent applications in the United States of America (USA) and in other rubberwood producing countries such as Thailand, Indonesia, and Singapore (#180413).

Licensing and commercialization

With technology transfer playing an important role in the Malaysian government’s IP strategy (Institute of Technology Management and Entrepreneurship, 2006), FRIM relies on technology transfer and licensing for commercialization. Patents allow the organization to make licensing agreements, and in 2010 FRIM signed such an agreement for use of its HTD technology with Techwood Industry Sdn Bhd (TWI), a larger rubberwood furniture manufacturer in Malaysia. In an email interview with WJO, Mr. Omar Explained that with the licensing agreement in place, TWI secured a Ringgit (MYR) 4 million loan (approximately US$1 million) from the Malaysian Technology Development Corporation to commercialize the technology. Unfortunately, this agreement did not lead to successful commercialization.

A few years later, Advance Low Pressure Systems (ALPS), another Malaysian timber company and TWI’s technical advisor, approached FRIM with an offer to scale up the use of the HTD technology and increase commercialization. ALPS believed they could be successful, and in early 2013 they signed a licensing agreement with FRIM that gave ALPS exclusive rights to the use of the technology in Malaysia. In just a few years ALPS was able to successfully commercialize the technology in a number of timber yards throughout Malaysia. FRIM and ALPS followed this up with an exclusive licensing agreement for commercialization in Thailand and the construction of an R&D center in the country to investigate other types of timber that can be treated with the HTD system. By 2015 FRIM was continuing to identify other commercial uses for its invention in rubberwood producing countries via investing in further licensing efforts.

Public health and environment

Many studies have found that borates do not pose a significant risk to the environment and public health and have low toxicity (3rd (1999) and 4th (2002) International Conferences on Urban Pests and Fernando Pessoa University (2010)). In response to the EC’s decision to classify borates in Category 2, the Malaysian government argued that this decision was made due to the production processes (Government of Malaysia, 2007), in that the EC claimed inhalation in the workplace could be toxic (Rin Tinto Minerals, 2007). While a risk assessment and opinion by the Scientific Committees on Consumer Safety (SCCS) of the EC deemed borates to be safe (SCCS, 2010), they remained in Category 2.

Despite this, FRIM’s HTD technology eliminates all risk as the method does not use borates or other chemicals or preservatives and is a safer method for both the environment and public health (according to FRIM). By 2012, there were over 2,000 furniture companies in Malaysia using rubberwood for their products (The Borneo Post, 2014), and if all of them utilized HTD technology potential environmental or public health risks could be significantly minimized. Furthermore, the method results in a greater production capacity per month of 210 tons compared to 100 tons for other methods (Commonwealth Forestry Association, 2014) and the average time it takes to process timber has been reduced to 2 days from 12 (according to FRIM). This increased productivity and reduced processing time could mean the use of fewer fossil fuels during other aspects of timber production – such as machinery to move timber and fuel required to heat it – thus potentially decreasing a processing center’s carbon footprint and benefiting the environment and the overall health of populations close to such processing centers. In addition, using the HTD method could ensure continued use of rubberwood in various products instead of rare tropical trees, which could lead to less deforestation (World Wide Fund for Nature).

Business results

Although FRIM’s first attempt at transferring its HTD technology met with negative results, a second agreement with ALPS proved successful, with two HTD treatment centers in Telok Gong, Malaysia, established by 2013 (FRIM, 2013). With additional commercialization aimed for Thailand and other rubberwood producing countries, FRIM’s innovative HTD technology has earned the organization and its R&D team positive media attention and a number of awards, such as the National Innovation Award (2013) and FRIM’s own Director General’s Innovation Award (2013) (FRIM, 2014).

In 2014, the first products made with HTD-processed rubberwood were successfully marketed on a trial basis to the IKEA (Thailand) department store chain and other companies in countries such as Australia, China, and South Korea. By the end of 2014 FRIM’s HTD technology was poised to be commercially successful in Malaysia and many other rubberwood producing countries.

Solving a problem with the IP-treatment

Responding to new regulations that could significantly threaten Malaysia’s timber exports to a major market, FRIM researchers were able to successfully invent, patent, and commercialize a new technology. Utilizing the IP system, the organization successfully transferred this environmentally friendly technology to industry partners through licensing agreements. Due in part to this strategy and a climate in Malaysia that is conducive to the protection of IPRs and technology transfer, FRIM’s innovation could possibly make a lasting contribution to the domestic and international timber industry.

Source: WIPO

Client Focus

Client Focus