Background

Until the late 1980s Jim Frazier was shooting wildlife films for David Attenborough. He was frustrated with the limitations of the lens available in the market then, and set about making his own.

“Wildlife is very unforgiving – there is no time to set up the camera and position the shot the way you want it. As well, with small subjects, such as insects and spiders, it’s very difficult to get both the subject and background in focus. I wanted it all in focus and I needed a versatile lens which would allow me to rapidly get the shots I wanted.”

Physicists at Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO) said it was impossible, and the Export Market Development Grant board refused to back the project, but cameraman Jim Frazier went ahead anyway and invented a new lens which has revolutionized the international film industry.

Invention

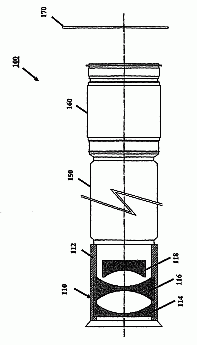

In the 1980s Frazier kept on rebuilding the lens and, with much trial and effort, formulated a lens with deep focus and a single swivel on the end. The optics to do this is very complex but he began to get positive results.

Frazier’s lens has three revolutionary features:

- a “set and forget” focus which holds everything, from front of lens to infinity, in focus;

- a swivel tip so that, without moving the camera, you can swivel the lens in any direction, completing a sphere if need be; and

- a built-in image rotator. This allows the image to be rotated inside the lens without spinning the camera.

The Frazier lens provides a massive depth of field technology allowing the foreground and background of an image to be in focus. It is a brilliant invention and when Frazier began using it in his work, it did not go unnoticed. Nobody had seen the sort of depth and clarity of filming he was achieving, and his work was unique.

Partnership

In 1993 Frazier was invited to speak at Montage 93, an imaging conference in the United States. Immediately after his speech, cinematographer John Bailey and the head of the American Society of Cinematography, Victor Kemper, contacted him and expressed their interest in Frazier’s new lens. In order to know the how the lens worked and how the output was, they requested Frazier to make a video with the lens. Once they got the video tape, they showed it to Panavision, the largest camera lens maker of the world. Within days, Panavision was knocking on Frazier’s door.

At this point Frazier thought that he should hire a lawyer for securing the intellectual property (IP) rights for his invention. He contacted Peter Leonard, a high technology international contracts lawyer with Gilbert and Tobin in Sydney, to do this job.

Initially Panavision sent Mr. Frazier a standard three-page contract, but his lawyer advised him not to sign it. Peter Leonard rewrote the contract and Frazier sent back a 30-page document to the camera-making company. The lawyer not only protected his invention but also helped him to negotiate a very formidable deal with Panavision, regarded as the best lens manufacture in the world.

The contract was structured so that Panavision could never come back and say that they had already known about the optics used in the lens. They met with Frazier on neutral ground in Hong Kong (SAR of China) and the company had to sign a confidentiality agreement before they saw the lens. Panavision was licensed to produce and market the Frazier lens.

Patents

“The deal was that Panavision would patent the device, at their cost, but that I would own the patent”, Frazier said. According to the contract, Frazier’s own film company, Mantis Wildlife Films (Mantis), gets a set fee for every Frazier lens that Panavision makes, and, when Panavision rents them out, a percentage of the rentals goes to Mantis.

A patent in the United States was granted on March 10, 1998 for the lens. Subsequently Frazier has obtained several patents in Australia and other countries for this lens as well as for other similar inventions relating to optical systems.

An important issue relating to Frazier’s patent application in the United States is that Frazier did not follow proper application procedures which later led to some critical problems. In order to demonstrate the features and uniqueness of the optical system and how it distinguished from prior art, Frazier submitted a user instruction video for the Frazier lens. When the patent was issued for the Frazier lens, Panavision and Frazier brought a lawsuit against Roessel Cine Photo Tech, Inc. for violating the patent. At the trial, it was discovered that the video Frazier had submitted as part of his patent application had been created with a different lens. The court ruled that the video was misleading for the patent examiner and, hence the patent was declared unenforceable for inequitable conduct. Patents in other countries, however, have not faced any problem.

Business Results

When Frazier first showed his lens to Panavision they could not work out how it was done. But they recognized its value. At more than US$ 1 million, this would have been one of the biggest patents ever taken out by Panavision but the returns are already rolling in. Nearly every second commercial made in the United States uses the Panavision/Frazier Lens and many in the feature film area will not go on a set without it.

The benefits to the film industry are huge. Quite apart from the unique abilities of the lens itself, it has dramatically lowered production costs. What used to be a three day shoot now takes only one day because Frazier’s lens has done away with the need for teams of people to rig up complicated setups every time the director wants a new angle. It’s as simple as adjusting the swivel tip. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences awarded a Technical Achievement Award to Frazier for his lenses.

Innovation and Patent Protection as a Gateway to Commercial Success

Frazier’s story shows that an individual’s innovative efforts, with due protection of intellectual property, can generate massive commercial success. The partnership with Panavision was in the interest of both parties, and both benefitted from it. For the cinematographic world, the revolutionary lens opened up options that previously were believed to be impossible.

Source: WIPO

Client Focus

Client Focus